An Interview with Karen Traviss - Gears of War Novelist and NYT Bestselling Author Part 2 (Ethics of the Reader)

Traviss tackles how ethics bleeds out of her work

Welcome to the 2nd part of what looks to be a 4-part interview series with writer Karen Traviss. If you have been following along for the last 3 months, I have fixated on Traviss’ work with the Gears of War franchise and how important her role has been in the lore we know today for the series. Karen is a treasure trove of insight in terms of the business of being a writer and what it means to think critically of the work you create.

For the first post I wanted to give insight about who Karen is with her love for anime but not what anime she likes but WHY she likes anime. I think it’s important for actual, established writers to explain the core, fundamental reasons why anime is a wonderful medium for storytelling. I mean, I can say it but y’all think I’m talking about girls with big boobs and Pikachu so I like to have backup here.

But also I wanted to poke her brain about a character like Bernie Mataki who was created by Traviss and is part of the series’ lore still.

For this next question, I wanted to get at the core issues of Gears - and that is ethics. As Traviss will point out, the ethics part comes down to the reader and their internal struggles with decisions made by characters in the books/games. The rotating politicians and people in power in Gears make choices that turn my stomach but does that make them good? Bad? Evil? Is it just a spectrum we have created to justify actions or judge others to make ourselves feel better?

There are complicated ideas tossed around in Traviss’ books and she presents them more matter of fact than inserting her own feelings on the subject (which is the smartest thing to do) because then the reader is questioning the characters and not Traviss.

Anyway, enjoy this response from Traviss.

Jesse: I got a friend of mine to read Aspho Fields and he was amazed by the climax of that book. It gave him so much more context to the eventual fate of Dom in Gears 3. It’s truly a remarkable novel as are the ones that follow that you wrote. My whole mind has been filled with Gears-stuff for 3 months and pretty much all because of your writing!

Recently I spoke with Jerry Oltion who wrote one of the novels for the Unreal game (a PC game from 1998). That was also handled by the Epic guys (sorta – in the baby years of Digital Extremes). But Jerry also commented on how helpful the game-side of the company was and how supportive they were of allowing the writer to open up the world. It’s great to hear that because you’re right, a lot of companies hire writers for their properties with specific models in mind. I’ve found the game-world to be a little more open.

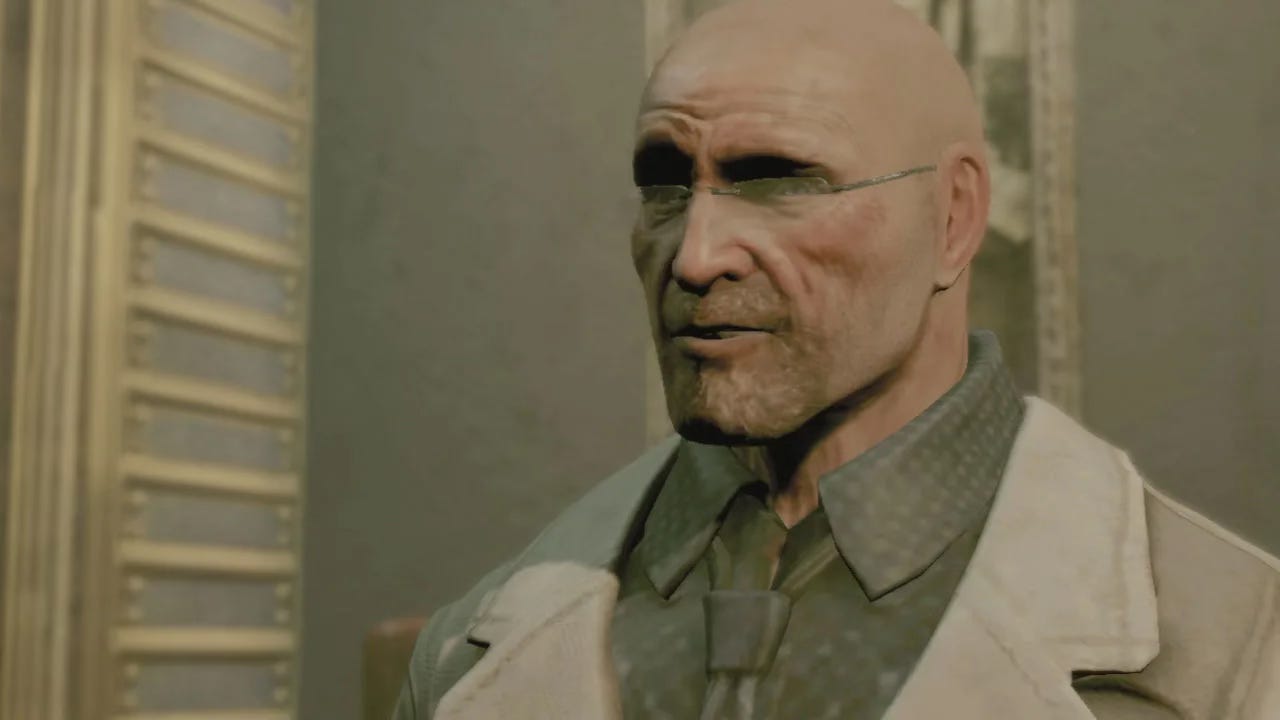

I want to talk about the Trio of Doom – Hoffman, Fenix, and Prescott.

I know you have been called an “ethicist” by reviewers because you deal with larger implications for populations due to the acts of a few. I think ethics are a rotating theme in the 5 Gears books you wrote. Between The Hammer of Dawn, the abandoning of Vectis, Adam Fenix’s work with The Locust and the creation of Azura, the people in power here truly move the pieces for everyone else. That is true with politics in general, I guess, and with other sci-fi properties, but I was wondering how you approached both humanizing the 3 men mentioned above while also painting their sins so clearly. Anvil Gate blew my mind at the end once I understood what Hoffman had actually done to the Indies.

Traviss: First let me say I had to re-read large chunks of Anvil Gate for the first time since I wrote it and I'm ashamed (but not surprised) that I found I remembered very little of it. It was one of those "Blimey, did I write that?" evenings. Yes, I did. When I say I erase my mental hard drive after a project, I'm not joking. So I'm hoping I've accurately recalled the salient points I didn't get around to checking. (And the geography of the mainland. Aw, come on, it's been fourteen years!)

Everything I write is about moral choices, and I suppose it does come down to the impact a few people can have. But it's more about the focus on a few people out of necessity, rather than a point about power, because my style requires very detailed tight third-person POVs, and that limits how many I can keep going in a book. Eight is probably the maximum I feel can be comfortably handled when you're asking the reader to jump back and forth between minds. It gets confusing after that.

In ethics terms, I look at where we draw our lines between Them and Us – who we stand with and who we see as our tribe – and how we handle the complications that science and technology add to our decisions. Inevitably, with military SF, those dilemmas are related to armed conflict. But they're not about the great the good – it's ordinary people being called upon to do extraordinary things, and trying to rise to the challenge. If anything, my fiction is about the rank and file, the ordinary men and women who fight or build or toil. Fiction tends to ignore them. The Three Not-Really-Amigos, in their context of a broken, dying civilisation, aren't as powerful as politicians now, and far less powerful than corporations in today's real world. They're all floundering, reduced to ordinariness by the scale of the unfolding crisis, small fish in a shrinking pond. When humanity's vanishing, their actions will have huge consequences one way or the other, but they're still reduced to mortals. Just men – widowed, betrayed, scared, angry, helpless. But as one of the characters in my Nomad series observes about a threadbare superpower in similarly shortage-ridden Earth a little in the future: "....in a world running on empty, the man with a charged battery and a spare mag is king."

In hindsight, you can wonder how much effect their actions have even in that context, except for Adam's lambency cure. Hoffman thought he was responsible for some of the course of the Pendulum Wars because he held Anvil Gate by extreme means, but looking back on it, I think it changed the course of him, because that's why Prescott promoted him – he knew he'd have what it took to deploy the Hammer if necessary. (Which Hoffman wasn't aware of at the time.) Adam's WMD didn't stop the Locust and probably didn't kill any more humans than the Locust would have eventually if left unchecked, it just did it sooner. But yes, this was about saving Ephyra, not Sera, and some people will think that's wrong, and some will think it's the only course you can take in the end: save the guy standing next to you. You can't save everybody. And, on a purely practical level, the Hammer is targeting Locust and they're not in Ephyra at that time.

Prescott could only say yes or not to deploying the Hammer, but the maths would have been the same. (And don't forget Bardry. He was actually the third man when it came to turning the launch key.) Prescott, Adam, and Hoffman were dragged along in the wake of events rather than shaping them, except for Adam's cure, and without Azura and Prescott ending up there, he wouldn't have had the facilities to create it, so his choices were still limited in the end. So they did the same as every Gear and civilian were doing, albeit in slightly nicer surroundings: they stumbled from one decision to the next as best they could.

How do I humanise those three men? I don't have to. (And I don't think they're that different from any other human.) The reader does the humanising, because that's how my method works: I show the reader something none of us see in the real world, not even with our nearest and dearest – someone's innermost thoughts and motives, not what we think they are but what they actually are. You're in their heads, and you can move from one mind to another and experience just how differently each one sees the world. To recap on previous answers, I build characters, let them loose, and stick to what they'd really do, even if I don't like it or it takes me somewhere I didn't think the story would go. I know I use this phrase a lot, but it's a big computer model or a giant data set in my mind, and I'm trying to reproduce causality as close to how it works in the real world as possible. The only way to do that is a cross between being in each character's head and being their bodycam. I not only have to see the world through their eyes, I have to walk through their day with them and experience their physical world step by step, or I just get completely lost.

Once I've got that down in words, the reader can "live" that character: and when you're in someone's mind, you experience them as a complete person, whether human, alien or AI. I'm not saying that means you end up liking them or agreeing with them, just that you know why they're doing what they do, or at least understand them as much as they understand themselves. So I don't have to emphasise any of those facets to make a point. if I did, I'd have to have a personal opinion on the character in advance, and that would wreck my method. It'd be authorial intrusion, a helicopter view, and I don't know how to work that way when I'm relying on the characters to come up with the plot. Every one of us makes sense to ourselves, even if we're serial killers (no, that was just an example, I swear... ) so the characters make sense to themselves as well. Every character sees a different reality, too, so the reader has to choose whose they believe. The critical thing for me is to immerse myself in them and really understand what it means to be that character and how their past shapes their present, and then work out their possible interactions with the other characters. The whole thing rests on a simple question repeated thousands of times: "Okay, what would X really do next?" Not what's the most exciting or surprising thing to spice up the story, but what that man or woman would actually do. It's often the complete opposite of what most people think fiction is about. It can just as easily be that they don't do anything, but that's still a connection in an artificial casualty.

That might explain why I forget what's actually in my books once I'm done with them and reading them again is like reading it for the first time. I was in the characters' minds when I wrote it, so it all happened to "them." My half-arsed theory is that because emotional memory persists much longer than event memory (a survival trait, I assume) the character stuff is largely stored in emotional memory, and it's somehow separate from mine. I compartmentalise my brain and I don't know how I do that, but I really can firewall parts of it, which might be why I decided to give that ability to some AI characters, because it just seems such a computer-like thing to be able to do. Sometimes I'm prompted to recall stuff from my life that surprises me and makes me wonder how it's possible that I don't think about this event or that every minute of every day, because they're such a big deal, but I just don't.

Now, many writers dismiss the idea that characters aren't just versions of "you," and that you don't control them. All I can say is medical science has shown otherwise. Maybe all their characters are based on themselves and their world views, and if that's how they write that's fine, but they should accept that others write very differently. Yes, you really can suppress your own personality and take on another one at will, and it was demonstrated by (if memory serves) Manchester University in Canada. (I have the link somewhere. ) They monitored brain activity in actors while they read their role aloud and got into it, and the scans showed the part of the brain that houses our sense of "Me" becoming less active and another area taking over. That didn't surprise me at all, because I was having a natter with an actor while we were killing time at a convention, waiting to do our appearances. We were discussing how we worked, and when I explained how I created characters and wrote them, he said: "Oh, that's exactly the same as method acting. You're method acting in a written form." He knew exactly what I meant because he did it too. Actually, lots of jobs use that same skill: I don't know if you have to learn it or whether it's pre-wired in some people who just develop it further, but it comes down to thinking like the other guy. That's something you need to do in the police, marketing, armed forces, journalism, and a lot of other jobs where you have to be predictive and work out what someone else is most likely to do. (And of course some people in those jobs do it way better than others, and some are dangerously useless at it. But you see my point.) It's not the same as touchy-feely empathy ("I feel your pain") because it can just as easily be used to target an enemy and ruin their day with a big bang as to understand how it feels to lose a child.

So I sit there and think: what's it like to be Adam Fenix? Semi-aristocratic, old money, doesn't have to serve in the COG army but does, a scientist, a man who loves his son but is away a lot and wishes he could relate to the boy better. What does he do when he's seen too much of war and wants a different future for his kid? And what does he do when he loses his wife and stumbles across a terrible secret that's also incredibly exciting science, and he thinks science can deal with it? What's it like to be Prescott, the son of a politician, groomed and educated from childhood to take over that role, with responsibility for a nation suddenly dumped on him in the very darkest days his world has ever seen? What's it's like to be Hoffman, an NCO in a seemingly endless war between two power blocs, surviving a day at a time and effectively forced into an officer rank while he watches his troops – his friends – fall around him, running out of options, and the attrition rate is so high that he finds himself at the top of the decision-making pile because everyone else has been killed? (And remember those are the perspectives of the characters, not mine. I know that not all the top brass who vanished during E-Day fell down a grub hole, and they're living it up on Azura. So does Prescott. Hoffman and Adam don't. Also, Hoffman wasn't aware he was hand-picked.)

So it's not difficult for me to "become" one of them while writing their scene. All I have to do is concentrate, but that can be the hard bit. Interruptions distract me far more as I get older, and it takes longer to get back into the zone. I don't produce flow charts and decision trees; that would be a step outside and make me become "Me" again, and I'd lose the character connection. Every time I have a problem with a book, I can trace it back to not being fully immersed in the character, so I have to retrace my steps and sync up with them again. My entire technique relies on that. I'm nothing like my characters – to be honest, I'd hate to live next door to quite a few of them, and there's a couple I'd shoot on sight – but I have no opinions about any of them while I'm writing. That little non-me part of my brain is them for that period and I sometimes have to really shake myself out of it to change my template back to myself. It's only when I've fully detached from the book that I can see them from my own personal viewpoint.

Adam Fenix, Prescott, and Hoffman all end up doing things that cost lives. You might sit back and think, "Monsters... I'd never do that!" but you have no idea what you'd really do until you're in that situation. If you're living those guys' lives from inside their heads, you'll reach the point summed up by that perfect tagline from (I think) the promo for Gears 1: "Understand what a world had to do to survive." That, for me, was the touchstone for the whole thing. I had to understand that desperation in every character to know what they'd do and feel next.

Adam actually has some choices that the other two don't. He knows about the grubs but decides to keep it to himself, which is overconfidence in his own ability to understand the situation and the arrogance of the expert class. He thinks he can persuade the Locust not to emerge because he'll find a way to destroy the Lambent, forcing them out. He's actually quite modest for someone who's got money and influence; he chooses to risk his life on the front line when he could get out of it, he genuinely believes that developing a Great Big Scary Deterrent to end all wars is the best hope not only for his son but the whole world, and he doesn't run from his responsibilities when it all blows up in his face. But he still has that hubris. (I still wonder if his wife was worse, though – what exactly did she know before he did?)

Very early on, when I joined the Gears team, Adam was already earmarked to die at the end, but they hadn't decided how. I remember saying to Rod Ferguson that Marcus losing his dad twice would be an unimaginable trauma for him and that it was the kind of challenge I'd love to tackle in the books. When it got to Gears 3 and I was in a position to write that in a different medium, I argued for Adam meeting his end by infecting himself with lambency, sacrificing himself to test it and get data, knowing that if it worked, he'd die. There's a long history of self-experimentation in the development of medicines, so it was realistic, but it was also redemptive, and the original premise of Gears was that Marcus was seeking redemption for abandoning his post. So Adam's decision to effectively do the ultimate penance fits with values passed from father to son. Adam does finally revert to the honorable man with a sense of duty who made one bad decision – keeping it to himself – just as Marcus has an uncharacteristically undisciplined moment and puts rescuing his father above the lives of his comrades. I don't think I ever fully worked out why there's this destructively impulsive streak in father and son that we never see again, but given how tightly they both keep a rein on their emotions, it might have been that rigid self-control finally ripping apart. So the Hammer of Dawn isn't Adam's biggest sin. By the time the grubs are unstoppable, it's the only option, and maybe it would have been even if he'd revealed their existence and the COG had launched a preemptive attack.

Prescott and Hoffman really do have no other choices. They can see what not deploying the Hammer will mean. The world will be overrun and humanity will be wiped out. (Remember, this is what they see, not a helicopter view based on hindsight by me or anyone else. This is exactly how it looks on the ground. There's far less visible in any situation while you're in it, at any level.) They argue, but they all know they're out of options, and Prescott and Hoffman share one quality with Adam: a sense of duty, even if Adam veered into thinking science could fix everything. (But it does in the end, so is he really wrong?) Hoffman knows his wife is going to be killed and there's nothing he can do about it. He's good at his job but he hates the requirements of it and would jump at the chance of being a sergeant on the front line again – except that means shirking a responsibility he's been given, and he won't do that. On top of all the other agonizing decisions he's had to make in the past, it's a miracle that he doesn't lose it at that point. But he's going to do his duty until it kills him. Prescott knew what he did at Anvil Gate and that he'd be able to face the Hammer of Dawn if he was Chief of Staff. In a way, the two men have a few things in common. Hoffman can't fault anything Prescott's done but still loathes him. Prescott doesn't like Hoffman but he respects his ability and integrity.

Prescott might be economical with the truth, and he might look like the typical politician who screws things up and saunters off, but he's made of sterner stuff. The process of writing him was educational. In the real world, I spent too long around politicians in a previous existence and I have zero tolerance for them now. (I can think of only six, maybe seven, I'd allow in my lifeboat. Some of them might need to be edible, though.) Regardless of party, they're mostly a single caste of affluent underachievers, and too many have never worked outside of politics or a closely-related ivory tower. (Harsh? I haven't even got started...) Remember: normal people generally don't go into politics, and the few who do so for selfless reasons because they want to right wrongs are either sucked into the morass and become part of it or get broken because they refuse to play the game. But Prescott seems to be more in the mold of the Victorian MPs and aristocrats who felt their privilege came with an obligation to do something positive for the country, a life of "good works." From what we know from Gears 1 and 2, he doesn't actually do anything wrong, and the more you examine his options on paper, the more you see how little room he has to maneuver. He tries to destroy the Locust but fails, and now it's too late to stop them and the Lambent as well.

All he can do is buy time for someone else to come up with a new solution and keep as many people alive as he can in the meantime to rebuild society if they survive. If he'd been cowardly and useless, he'd have left for Azura after E-Day with the rest of the elite and not looked back. Instead he stays put to carry on doing his job and even risks the move to Vectes. For all he knows, he might die there. It's a very long way from Azura, too. But he feels compelled to stay at his post. Now that's a man who knows what duty means, even if he isn't likable. When he leaves Vectes – well, no Azura = no Sera. I think he had to leave when he did to get things sorted at that end. He knew the clock was ticking. Much of what we see in the books is the perspective of those who didn't know about Azura and when they find out, they're furious that while they were dying and scrabbling for scraps of food, the elite were apparently living it up.

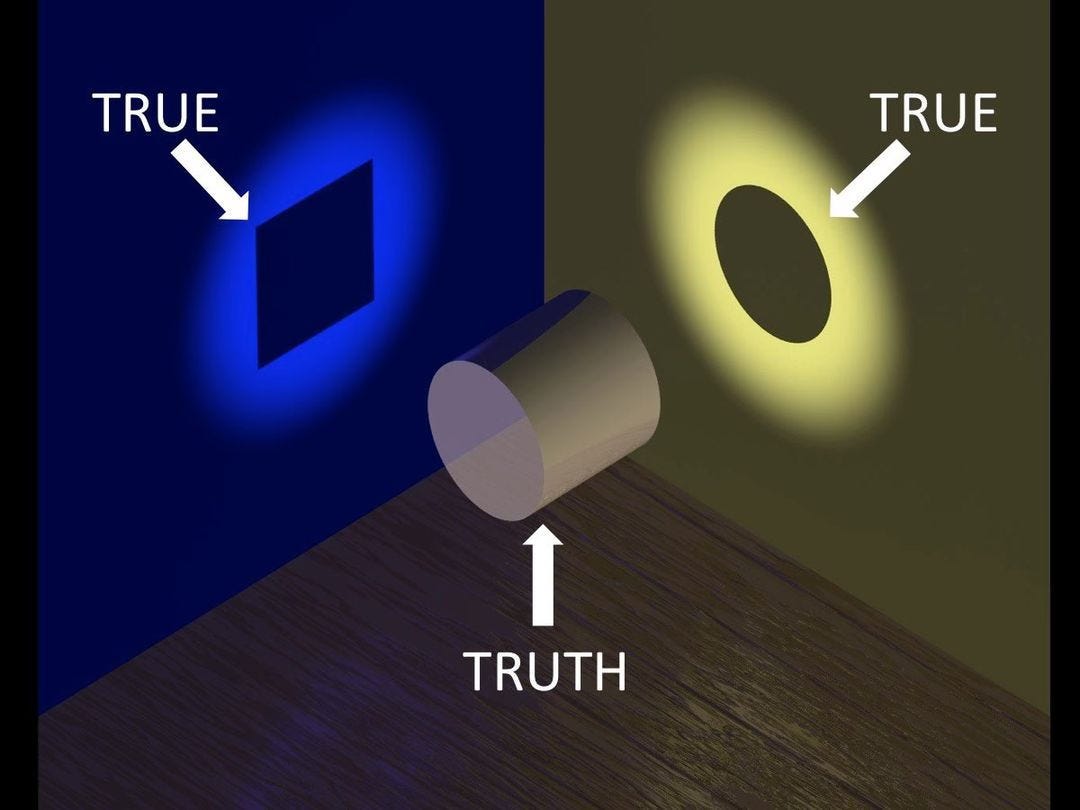

The best way I can describe it is via someone else's meme. It's a good one to live by.

(And, off topic... that rallying speech Prescott gives in Gears 2 is magnificent. I used to write the occasional speech and I know a solid gold one when I hear it. It made me want to rush out, vote for Prescott, and carve up a few grubs on the way. Respect to Josh Ortega for that.)

In Prescott's world, he never felt he had a choice to be anything else. His father mapped out his future, not because he was a horrible dad but because he thought the Prescotts had a duty to serve Ephyra and the COG. It was a responsibility, not their right, or a way to line their pockets, and the family had to carry that burden because their privileged life demanded they give their all in return. So just writing Prescott and having to think like him made me look at that more carefully. In both our countries, politicians come from a very narrow affluent demographic largely disconnected from the realities the rest of the population faces. They even seem to dislike the electorate. Being a politician has turned from a calling, or at least an intention to do no harm to the nation, into a career with a fat salary and expenses to be clung to at all costs. It's hard not to look at people who feel obliged to serve the public and wonder if the Prescotts of this world would do a better job. Being in a character's head has changed my mind on major issues more than once. I suspect it's a side-effect of shutting off my own views and sense of "me" for a while, which lets me see things I'd normally overlook. The books write me more than I write the books.

Hoffman and Prescott know what they have to do, and so does Adam Fenix. They're not saints, but they're not villains either. That describes most of us. They're just mortal men in a terrifying, unfathomable disaster. I know I keep saying I don't write heroes or villains, just people, but it's true. So I just show the whole character as they see themselves as well as what others think of them, and let the reader decide. That was what journalism was about when I was a working hack. Professional discipline meant being the public's eyes and ears, giving them information from all sides for them to make up their own minds, not telling them what to think. So this is the only way I know how to write. It's not wooly-minded moral relativism or any abdication of ethical responsibility like that. I've got strong personal views on right and wrong, and I know who my enemy is, but that doesn't have a place in my books. They're not manifestos. They're questions.